Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) was established in Chicago in the 1930s by three midwesterners. From its earliest days, the firm was immersed in both modernism and skyscraper construction: The city was, at that time, trying to build itself bigger and taller than New York. As early modernism trickled into the U.S. from Europe, SOM grew its business larger and larger, finding success in New York, then across the U.S., and ultimately world-wide. The firm has nurtured the careers of many great architects over the decades, keeping at all times a long roster of established names and new talent. By the turn of the 21st century, SOM was synonymous with skyscrapers, having designed many of the world’s tallest structures, including the current tallest, the Burj Khalifa. Here, take a look at some of the most iconic works that assert SOM’s dominance in the tall buildings market.

Manhattan House, 1951, New York By 1951, SOM had ventured outside of Chicago and entered the New York market confidently. Designed by partner Gordon Bunshaft, the Manhattan House was SOM’s first large-commission foray into modernism, and the city’s first white-brick apartment building. The 21-story structure’s huge balconies, clean lines, and impressive scale brought attention both to the firm and to modernism’s rise in American architecture.

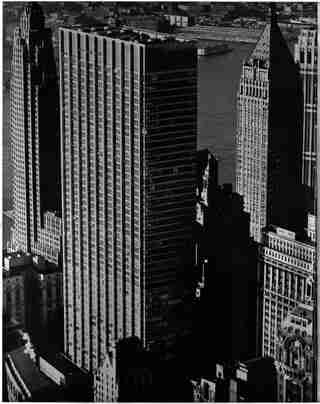

Lever House, 1952, New York

One of Bunshaft’s most significant contributions at SOM was his design for the Lever House in Manhattan. Today the tower may appear to be just another flat glass skyscraper, but the building, in fact, served as the prototype for the now classic look. The International Style emerged in the 1920s and ’30s in Europe and was known for its total lack of ornamentation and complete departure from, if not refusal of, classical architecture. By the early ’50s, SOM, via the Lever House, helped to make the International Style the preferred choice for big-city corporate skyscrapers.

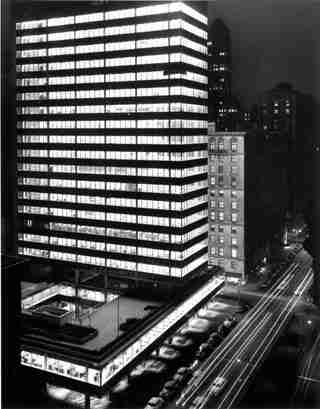

One Chase Manhattan Plaza, 1961, New York

The slender, shiny rectangle that rose above downtown Manhattan in the early ’60s was a statement of the alluring efficiency of 20th-century American capitalism. Delegating most of the site’s footprint to an elevated public space, the massive One Chase Manhattan Plaza stands improbably thin. Bunshaft set the building’s steel beams on its exterior, clad with glass and aluminum.

Cadet Chapel, 1962, Colorado Springs, Colorado

In the early 1960s, SOM was commissioned to develop a master plan for the U.S. Air Force Academy’s campus in Colorado Springs. The high point of the plan was, far and away, the Cadet Chapel. The structure’s nave was formed by 17 aluminum spires stacked as sharp triangles, creating a form that echos church design of eras past in an unapologetically modern way.

John Hancock Center, 1969, Chicago

This tapered tower is an enduring landmark of the Chicago skyline. By 1969, SOM’s hometown had for decades been a sandbox for modern high-rises and skyscrapers. The John Hancock Tower was the city’s tallest building when completed, and was the world’s first mixed-use skyscraper, featuring commercial and office space on the tower’s lower (and wider) floors and condominiums on the narrower upper floors. Its crisscrossed external beams are now an iconic Chicago form.

The Willis Tower, 1973, Chicago

Completed in 1973, the Willis Tower (formerly the Sears Tower) reigned as the world’s tallest building for nearly 25 years. The 110-story tower was designed as a bundled tube building: Nine massive tubes are bundled in a tight square, topping off at various heights. The building signaled Chicago’s dominance in the international skyscraper scene.

Chase Tower, 1987, Dallas

Architect Richard Keating, working for SOM, delivered postmodernism in his 1987 Dallas skyscraper. The curved roof and keyhole opening, however clean, were a major departure from the International Style. Postmodernist buildings henceforth saw a return to ornamentation and classical reference.

Jin Mao Tower, 1999, Shanghai

Certainly a far cry from SOM’s International Style towers, the ornate, pagoda-like structure was built as China’s tallest building. The home of the Grand Hyatt Hotel, the site played to SOM’s full-service strengths, housing courtyards, retail programming, conference spaces, and a reflecting pool.

Time Warner Center, 2004, New York

The Time Warner Center on New York’s Columbus Circle was a huge commission, as the twin glass buildings were built atop a ground-level luxury shopping mall. The mixed-use tower was a complex but successful attempt at creating a new Manhattan destination for business, shopping, lodging, and residential real estate. The glass façade plays interestingly on angles and light reflection, something that can be seen in many recently built skyscrapers.

Jianianhua Centre, 2005, Chongqing, China

Aside from SOM’s deftness at large towers, the firm is well versed in designing sprawling centers. The Jianianhua Centre in Chongqing is a example of the firm’s preeminence in urban design and planning. Chosen by officials of one of the world’s fastest-growing cities, SOM developed the plaza at the heart of a carefully planned commercial center and public space, which resulted in a Times Square–like LED-clad commercial mass.

Burj Khalifa, 2009, Dubai

The Burj Khalifa is quintessentially SOM. By far the world’s tallest building, the skyscraper has 154 usable floors, and the tapered structure is a more ornate update of the Willis Tower’s bundled tube design. It’s shiny, it’s bold, and it’s impressive.

One World Trade Center, 2013, New York SOM was again at the heart of international skyscraper design during the much-watched rebuilding of the World Trade Center in New York City. Now the tallest building in the Western Hemisphere (and Architectural Digest’s home), One World Trade Center, like the Time Warner Center, plays with light in interesting ways. From a distance and at certain times of day, the tower reflects the sky’s color almost perfectly. Viewed from the ground at its base, the tower’s unique angling makes it appear to be a massive isosceles pyramid.

Denver Union Station, 2014, Denver

Adding to its portfolio of transportation hubs, SOM expanded Denver’s Beaux Arts train station into a massive complex, converting some 20 acres of old rail yards. While the focal point of the project is a sinuous, open-air train hall, revamped amenities include an underground bus concourse, a light-rail terminal, and a network of pedestrian paths and public spaces.